CeCe dug up an interesting article from 2006 in Baltimore’s City Paper (no longer available online). Here she recounts the bizarre tale of how Joseph Di Giorgio escaped death at the hands of his banana-importing rivals.

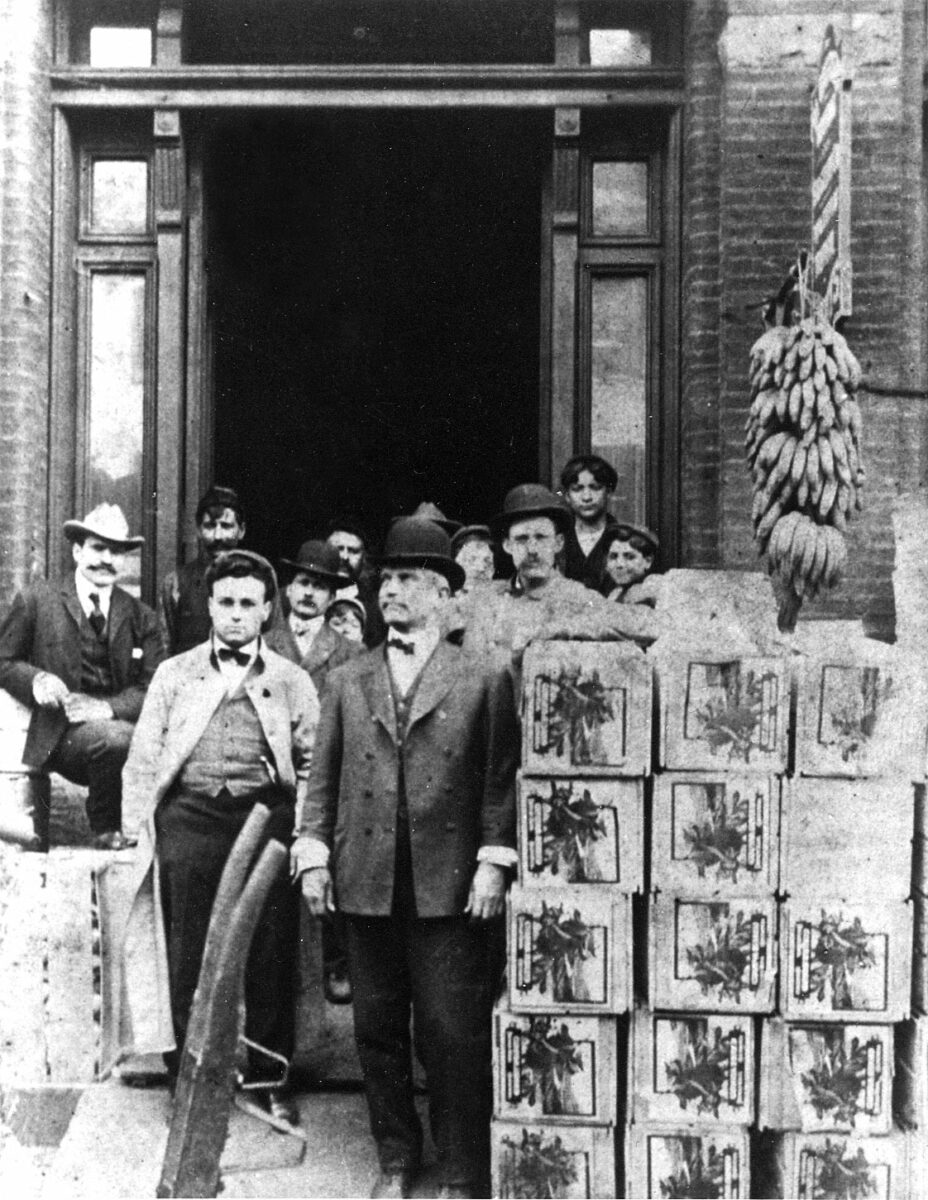

Reporter Brennan Jensen spoke with the descendants of local importing and shipping giants Antonio Lanasa and Alfred Constantine Goffe. Sicilian Lanasa and Jamaican Goffe were accused of masterminding a Black Hand assassination plot against rival Sicilian banana importer Joseph Di Giorgio in December 1907.

The story of the Lanasa–Di Giorgio feud is a fascinating one, and in some ways an echo of the New Orleans Matranga-Provenzano dock warfare of the late 1880s and early 1890s.

Di Giorgio, Lanasa, and Goffe were briefly business partners in the Atlantic Fruit Co. But Di Giorgio reportedly made a secret deal with the monopolistic Boston-based United Fruit Co. and threw Lanasa and Goffe out. (They subsequently recreated their own independent shipping firm.) He also allegedly caused the death of a Pittsburgh-based Black Hand extortionist, referred to as Rea or Rei, who was demanding money from him and his business partners. Di Giorgio might have had underworld connections. His willingness to go toe-to-toe with mafiosi speaks either for his connections or for his great personal courage.

Rea’s Black Hand organization reportedly had branches in Baltimore, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Buffalo, and Brooklyn. The organization, understandably upset at the loss of Rea, welcomed the opportunity to get even with Di Giorgio and his allies. Assassins were hired to kill Di Giorgio: Joseph Sunseri of Pittsburgh, who actually shot down Rea (a Salvatore Sunseri, possibly related, was one of the New Orleans mafiosi accused in the 1890 assassination of Chief of Police David C. Hennessy), and Nunzio Battaglia of Pittsburgh (whose name was recorded in many newspapers as Battaglonia). The assassins were to be paid $30,000. It was widely believed that Lanasa instigated the hit, deciding, “If we kill Di Giorgio, I will be the banana king of Baltimore.”

The hit against Di Giorgio was botched. A couple of sticks of dynamite were placed under the kitchen area of his residence in the suburb of Walbrook when he wasn’t home. The explosion damaged the kitchen, a pantry, and a bathroom but hurt no one. Investigators tracked the perpetrators to Pennsylvania, Ohio, and western New York.

Salvatore Lupo, former employee of Lanasa, was arrested in Buffalo. He made a full confession—though he only admitted to being part of the conspiracy to blow up Di Giorgio, claiming he arrived in Baltimore just after the bomb exploded—and became a government witness. John Schiatta, AKA Scarietta, was arrested in Cleveland. He fought extradition for two weeks but was eventually turned over to Maryland authorities.

Lanasa and Goffe were both arrested and indicted, largely because of Lupo’s testimony. Lupo said Lanasa ordered the hits but Goffe was responsible for delivering the payment and discussed providing legal fees if the assassins were caught. Goffe unluckily had arrived in Baltimore from Jamaica just hours before the explosion at the Di Giorgio residence. Some Lanasa supporters suggested that the indictments might have been due to the fact that Thornton Rollins, vice president of Di Giorgio’s Atlantic Fruit, served as foreman of the grand jury.

Goffe was indignant at the time of his arrest and threatened that he would have the English fleet sail into Baltimore harbor if he wasn’t released.

The defense was represented by one of those legal dream teams that seem to come together for mob cases. Lanasa was defended by Senator William Pinkney Whyte (Whyte had also been Maryland governor, mayor of Baltimore, comptroller of Maryland, and the state’s attorney general). Goffe was represented by George Dobbin Penniman, hired by the British consul Gilbert Frazier (Penniman’s family roots in Maryland went back to the 1630s). The case against Goffe was later dropped because Lupo had stated that all conversations relating to the hit were conducted in Italian. Goffe didn’t understand Italian.

During the trial, the Black Hand connections of Lanasa employees was discussed. In a number of instances, the prosecution referred to a Black Hand supreme boss who lived in Brooklyn. Whenever a Baltimore Black Hander would offer to help out a Black Hand victim, he would note that he had to travel to Brooklyn to get the boss’s OK. The boss’s actual name was not revealed, but an alias something like Camelia la Rosa was used. It was later decided, but never confirmed, that a New York barber named Tony Calcagno was actually Camelia la Rosa. Calcagno was found shot to death in New York in early February 1908. A Baltimore detective went to New York to view the body and made a probably baseless announcement that the leader of the Italian-American Black Hand underworld was dead.

Lanasa was eventually convicted, not of attempting to murder Di Giorgio, but only of damaging his property. Even that conviction was subsequently thrown out because it was based almost entirely on the testimony of indicted co-conspirator Lupo. Also a factor was Lupo’s insistence late in the trial that his confession had been coerced by detectives.

Lanasa and Goffe made plenty of money in the coming years, before breaking up the firm in 1915. Goffe returned home to Jamaica and became a wealthy landowner there. Lanasa continued to earn a fine living in various fruit businesses. The two men died in the early 1950s.

Di Giorgio’s rags-to-riches story was just getting started. He left Baltimore to go back to New York, where he had first landed after leaving his native Cefalu, Sicily (on the northern coast, east of Palermo). He left his brother Rosario behind to tend to the Baltimore business. After a short time Di Giorgio ventured west to California. There he bought up large tracts of land near Bakersfield, as many as 40,000 acres by 1937, and entered the domestic produce business. His farms became enormously successful until labor problems occurred in the mid-1940s. (The unionization of the region’s farm laborers is documented in Ernesto Galarza’s “Spiders in the House & Workers in the Field.”) Whether these labor problems could be linked to underworld activity is not known, and mob history in the region remains sketchy.

The 73-year-old Di Giorgio had apparently had enough by the time a 1947 strike crippled his company. When the strike was resolved, Di Giorgio sold the farm to S. A. Camp. He lived his few remaining years in quiet comfort, dying in 1951. A community just outside Bakersfield bears his name.

Family connections

My father was Salvatore Di Giorgio and in the 1950's he managed the Baltimore Fruit Auctions for the family business Di Giorgio Fruit Company. One person he had many contacts with was Charles Nosser in New York. He was very much admired and respected by my father. So glad to have read about your family connections via the website created by Elliot Grant.

Charles Nosser and his close relationship to the DiGorgio Family

Charles Nosser was my fathers paternal uncle through marriage. My dad and several of his uncles and first cousins were Exec's in the NY Fruit Auction and also auctioneers. Charles Nosser was its President and CEO…from family lore and some digging into the DiGorgio family, Nosser was a close confident and advisor to the family.

Jamaica Fruit & Shipping partnership with Di Giorgio Fruit Co

My granfather Charles Edward Johnston did a lot of business with DiGorgio

do you have any records of this?

Charlie Johnston

Connection

I do not, but I can check in with my husband's family.

thanks for writing,

Anne