Gunner recalls 26 bombing missions with bird’s-eye view of war

By Pat van den Beemt, pvdb@comcast.net, The Baltimore Sun

May 30, 2012

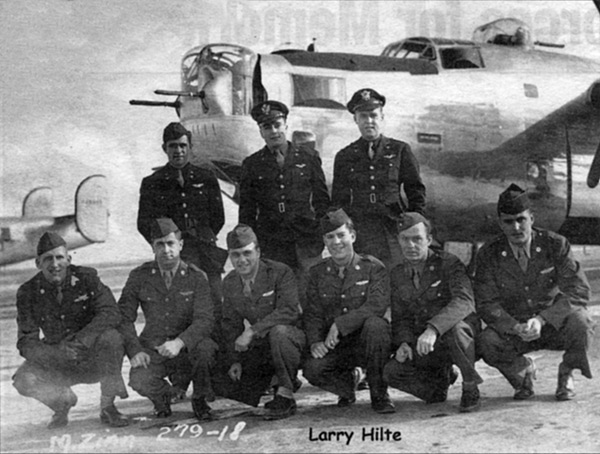

Larry Hilte had a date with destiny on Valentine’s Day, 1945. Then just 19 years of age, the Marylander flew his first combat mission onboard a B-24 Liberator bomber.

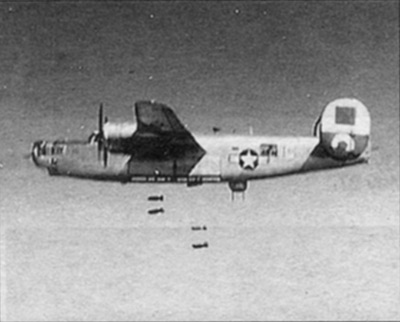

He and a crew of eight left Spinazzola air base in Italy and headed for Vienna, Austria, where they dropped five 500-pound bombs on industrial targets.

Hilte had an unobstructed view of the bombs plummeting to earth. He was a ball turret gunner who spent each bombing run in a small sphere that hung from the belly of the plane.

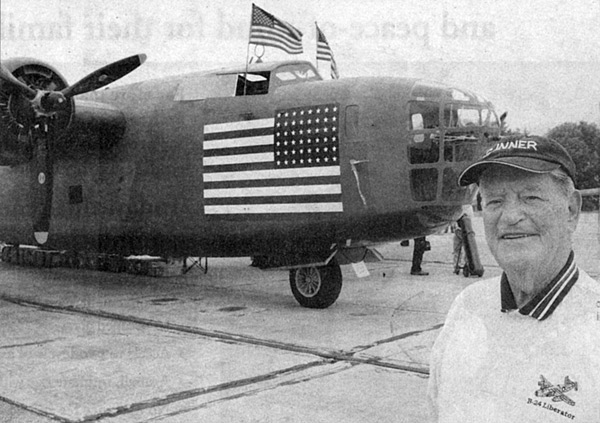

“I got the job because I could fit in the space,” said Hilte, a Towson resident, during a visit on May 23 to see a B-24 Liberator bomber on display at Martin State Airport.

“I was 5’5″ and 124 pounds soaking wet,” he said. “There wasn’t room for anything more than me and the machine guns. My parachute was up in the plane. I took off my flak jacket and sat on it.

“I didn’t know enough to be scared. That’s just the way it was.”

Hilte, 86, lives in Towson, and before that spent more than 30 years in Timonium. He has no problem remembering his war experience, since he has kept records of the 25 missions he flew with the 15th Air Force 460th bomb group.

He said his last mission took him to Mestre in northern Italy on April 26, 1945. Twelve days later, the German armed forces surrendered.

Hilte knows the date, destination and duration of each run. Most round-trip flights took between six and seven hours, he said.

The ball turret was inside the plane during take-offs and landings. But as soon as 67-foot long plane took off, Hilte climbed in and was lowered.

“The guns were aimed straight down,” he said. “But I could raise them up and rotate them in a complete circle.”

The biggest danger came from enemy planes that came at the B-24 from below. “They would just fly right under you,” he said. “They were so close I could see the crew.”

His plane, “The Yugo Kid,” caught some flak from anti-aircraft guns fired from the ground. “You could stick your finger through the holes in the plane,” he said.

Hilte recalled being escorted on missions by the Tuskegee airmen, African-American pilots who had painted their planes’ tails red.

“We always felt safe when we saw those red tails,” he said. “We lost a lot of planes, but I never (personally) saw one go down.”

History and heroes

The plane at Martin State Airport last week is one of 18,000 B-24s made for the war effort. Just prior to the Memorial Day weekend, it was in Maryland on display by the nonprofit Commemorative Air Force, which maintains and exhibits World War II planes.

Hilte and his wife, CeCe Brooks Hilte, have seen the touring B-24 before, in Florida and Reading, Pa. It’s one of two B-24s still capable of flying.

“It looks smaller and smaller each time I see it,” Hilte said. “It’s amazing to think of all the hours I spent on it, either training or going on missions.”

His son, Larry Hilte Jr., and grandson, Brandon Hilte, who live in Pinehurst, Md., came with him last week to see the plane that’s such a big part of their family history.

“He’d tell me so many stories growing up that I became interested in military history, and I study it all the time,” said Brandon Hilte, 28. “He is my hero.”

Hilte was a Clifton Park High School graduate when he was drafted into the U.S. Army Air Force in November 1943. The 18-year-old had never flown but he wanted to be a pilot, so he was sent to Alabama for training.

The program was soon suspended because additional pilots were not needed. Hilte had two choices — infantry or gunner. He stuck with fighting the war in the air.

He and his crew eventually flew a brand new B-24, “Pleasure Bent,” to Italy, where it was promptly given to a senior crew. While Hilte’s “Yugo Kid” flew its sixth mission on March 1, 1945, “Pleasure Bent” was hit. It went down, killing the entire crew.

After his last mission in April 1945, Hilte was sent back to the U.S. and was preparing to fight in the Pacific when Japan surrendered on Aug. 15.

He was discharged and returned to Baltimore in December.

“This little guy from Baltimore got to see so much of the world and experience so much,” Hilte said. “But when I got back home and went to a bar and asked for a beer, the bartender didn’t serve me because I was only 20.

“After I told him where I’d been and what I’d done, I got my beer.”